Photios Kontoglou, the greatest icon painter of modern Greece and one of her most important theologians and literary writers, died in Athens on July 13, 1965. His death, during surgery, passed almost entirely unnoticed in America, even among Greek-Americans, but he was deeply mourned throughout Greece.

I was in Greece when he died and had the good fortune of seeing and talking with this great and holy man just five days before his “falling asleep.” The editor of an Athenian religious monthly asked me to write an obituary . . . I have undertaken to write this brief biography.

Photios Kontoglou was born on November 8, 1895, at Kydoniai (Aivali), on the west coast of Asia Minor, across from Mytilene. Kydoniai was a city consisting of about 30,000 Greeks and three persons—the district governor, the judge, and the tax collector—who were Turks.

Kontoglou came from a devout family, which had its own chapel containing precious articles including a carved ancient crucifix and a large panel icon depicting Saint Paraskevi. Many of his ancestors were monks, and an uncle, Stephanos Kontoglou, was abbot of the Monastery of Saint Paraskevi near Kydoniai. Stephanos was an important influence in Photios’s life. In his book Vasanta (1923), Kontoglou dedicates the chapter of translations from the Psalms of David “to the austere soul of the Hieromonk Stephanos Kontoglou, my uncle, whose virtue I perpetually have before me as a model and rule.”

The young Kontoglou was extremely fond of the sea, sailing, and the solitude of the deserted neighboring islets. He liked to live alone, like Robinson Crusoe. Daniel Defoe’s hero fascinated Kontoglou; he mentions him in many of his writings.

After graduating from the famous Academy of Gymnasium of Kydoniai, Kontoglou spent several years in Europe, especially in France, studying art and acquiring painting techniques. He lived in Paris during the First World War, where he first gained attention, winning prizes for his paintings and his writings. His first book, a novel entitled Pedro Cazas, was written and published there in 1919.

After the armistice, Kontoglou returned to Kydoniai. In 1920 he wrote a remarkable prologue for the second edition of Pedro Cazas which was published in Athens in 1922. In this prologue he set forth some of the basic ideas by which he abided ever after.

Persecuted by the Turks, he and his family went to Thermi, Mytilene, in 1922. Later he resided in Athens, but always lived on the outskirts, as he disliked the distractions of cities. When the Kontoglou family left Kydoniai, they took only the sacred articles mentioned above and a few Church books. These were his most cherished possessions. After his death his wife, Maria, fulfilling his wish, gave them to the Monastery of Saint Paraskevi at Nea Makri in Attica.

In Athens Kontoglou soon became well-known in literary circles as a result of his highly-praised book, Pedro Cazas. His reputation as a writer grew with the appearance of two additional books: Vasanta (a Sanskrit word meaning “springtime”) in 1923, and Taxidia (“Travels”) in 1928, and the literary and art periodical Filikh Etairia (“Friendly Society”) which he founded in 1925. Within a few years, Kontoglou had won an enviable place in the Greek world of letters, admired for his style—which is characterized by clarity, simplicity, vigor and warmth—as well as his remarkable observations and profound thoughts.

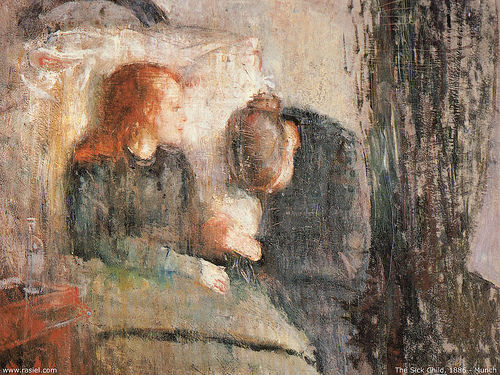

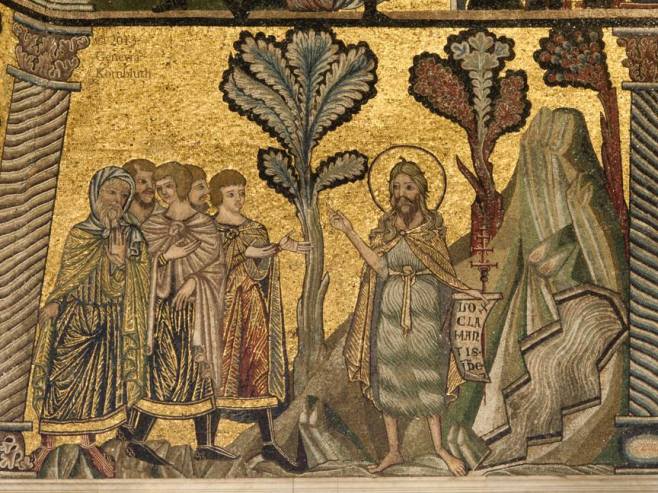

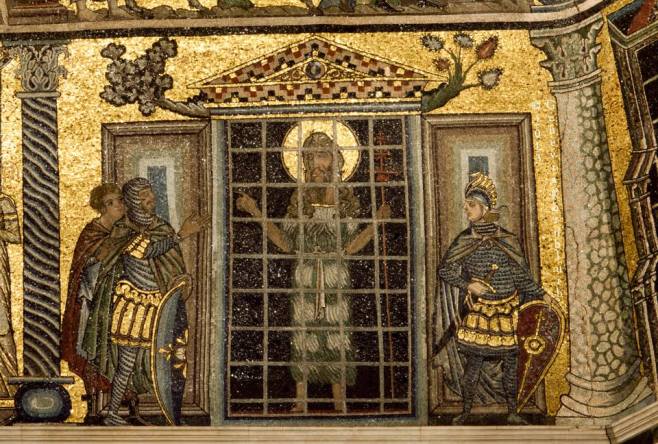

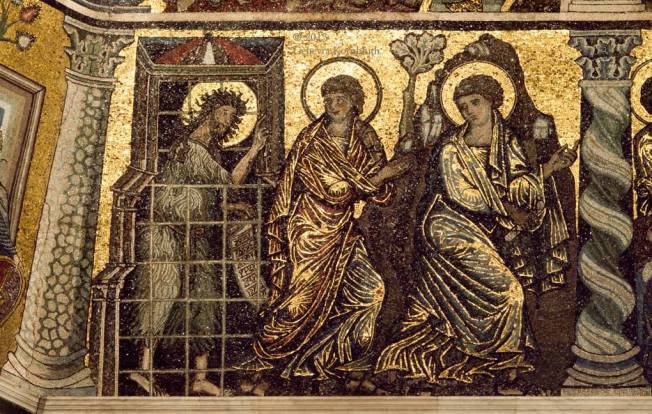

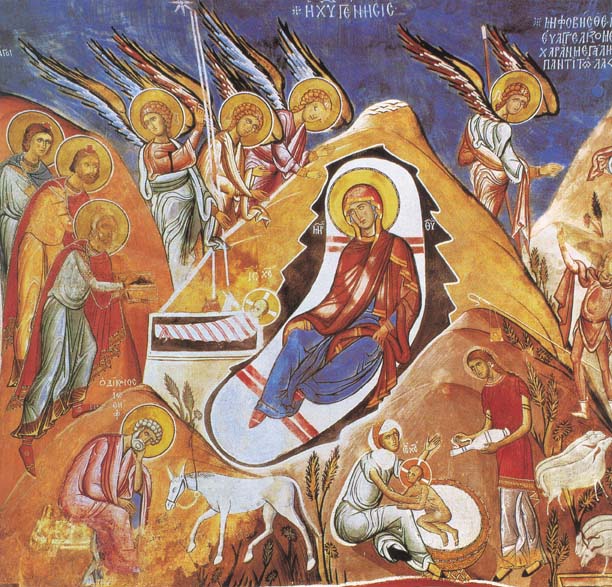

As a painter, Kontoglou was slow in winning recognition. He had to overcome difficult obstacles. After leaving Europe, he became increasingly impressed by the Byzantine traditions of painting and decided to master this style of painting. But he had to become his own teacher and learn the secrets of Byzantine art. He did this by reading old manuscripts and visiting Byzantine monuments, patiently studying the works of the old masters.

Further, Kontoglou had to overcome strong prejudice on the part of the public against Byzantine art. Having won their liberation from the Turks, the Greeks began to turn the West for prototypes in art, especially the adoption of European (particularly Italian Renaissance) models and techniques. According to the European view at that time, Byzantine civilization was a lower civilization, not worthy of serious study, and Byzantine art especially was lower, almost barbaric art. Kontoglou succeeded magnificently in overcoming both obstacles, but it took time.

The first obstacle was by far easier to overcome. He learned his most important lessons about Byzantine art at the Holy Mountain of Athos and at Mystra. It is significant that while at Athos, he wrote several chapters, the preface and profound concluding chapter on the fine arts of his second book, Vasanta. It was also at Athos that one of his three poems in this book was inspired by a Byzantine painting in a very old chapel there. His debt to Athos in his development as an iconographer is evinced by a volume published in 1925 containing photographs of copies, executed by him, of Byzantine frescoes at Athos; and also by the illustrations in two issues of Filikh Etairia that year showing panel icons of the Monastery of Iviron rendered by him.

Kontoglou visited Mystra not long after. He made copies of some of the wall paintings in the Byzantine churches at Mystra. He later worked there for a long time cleaning wall paintings in the Church of Peribleptos.

Comparing Byzantine and European religious art, Kontoglou says in his book Taxidia, “In the countries of Europe there are churches with paintings that are famous for their artistic merit; yet they do not have the mystery and the power of evoking contrition (katanyxis) possessed by the icons that were done by some unlettered and simple Byzantine painters.”

Around 1930, Kontoglou was appointed technical supervisor at the Byzantine Museum in Athens. He possessed both great love for the works in the museum, and technical knowledge for cleaning and preserving them.

In 1932, Kontoglou published a slender volume entitled Icones et Fresques d’Art Byzantine, with twenty plates of Byzantine panel icons and frescoes he copied. He continued to paint panel icons during this period.

During the later thirties, Kontoglou decorated three large rooms of the City Hall of Athens with historical frescoes. This was his first large scale work as a fresco painter, and his only extensive secular one. His next major achievement as a fresco painter was the iconographic decoration of the large Church Zoodochos Peghi at Liopesi (Paiania), a town near Athens. He began the work in 1939, but could not resume it until after the Second World War. When I met Kontoglou in 1952, he showed me the beautiful Byzantine murals he had painted at Liopesi.

Kontoglou wrote at least eight books between 1942 and 1945, during the war. Most are rather short. The longest and important is Mystikos Kepos (“Mystical Garden”) in 1944. His chapters on Piety (Theosveia) and Saint Isaac the Syrian are masterpieces, full of deep religious feeling. He speaks of other remarkable ascetics of Syria and Mesopotamia, and stresses the virtues of faith, humility and purity.

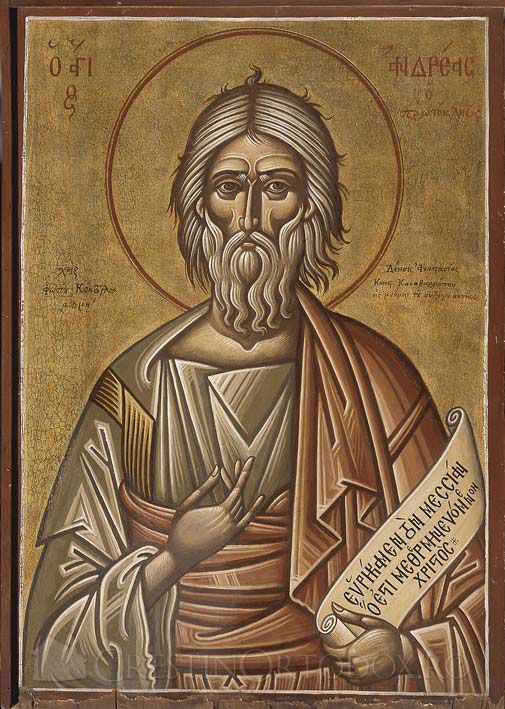

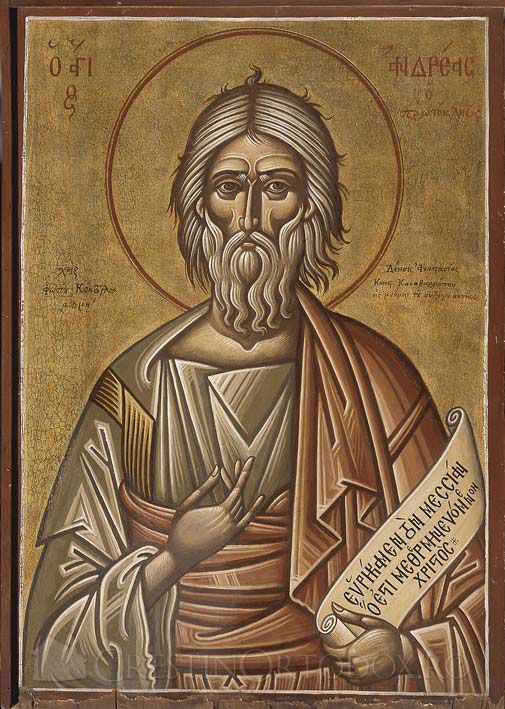

The most fruitful period for Kontoglou, as both painter and writer, was the last twenty years of his life. Assisted by several of his talented pupils, he painted numerous panel icons in churches in many parts of Greece, as well as in the United States and other countries, and many thousands of square yards of wall paintings. After the church at Liopesi, mentioned above, Kontoglou frescoed the entire interior of the Church of Saint Andrew off Patission Street at Athens. He did wall paintings for the new Metropolitan Church of Evangelismos in Rhodes and the Church of Saint George at Stemnitsa, Arcadia. Finally, he decorated with fresco icons the eastern apse, central dome, pendentives and barrel vaults below the dome, and other surfaces of the following Athenian churches: Kapnikarea, Saint George at Kypseli, Saint Haralambos in the park Pedion tou Areos, Saint Nicholas at Kato Patissia, and others.

Through these works, through the training of many gifted young artists in the techniques of Byzantine iconography, and through his long, luminous and spirited defense of Byzantine art which culminated in 1961 in the monumental two-volume work entitled Ekphrasis (“Expression”) in which he teaches the theory and practice of Byzantine iconography, Kontoglou succeeded in making this art prevail in Greece. His influence spread to America, where many churches have been decorated with panel icons, frescoes and mosaics by his pupils.

During the same period, he wrote such edifying books as A Great Sign (1945), with accounts of many extraordinary recent miracles at Thermi, Mytilene; The Life and Conduct of Blaise Pascal(1947); The Life and Ascesis of Our Holy Father Saint Mark the Anchorite (1947, translated in The Orthodox Word, no. 1, Sept.-Oct., 1966, with illustrations by Kontoglou); Fount of Life (1951), presenting brief descriptions of the lives and selections from the teachings of some of the great Saints of the Orthodox Church; The Holy Gospel According to Matthew, Interpreted (1952); Expression (1961); and What Orthodoxy Is and What Papism Is (1964). Kontoglou also translated into Greek Leonid Ouspensky’s L’Icone: Quelques Mots sur son Sens Dogmatique, and published it with a preface and notes of his own. Together with the young theologian Basil Moustakis, Kontoglou founded and edited Kivotos (1952–1955), a religious periodical concerned especially with Orthodox spirituality.

Kontoglou contributed many articles to various other periodicals and encyclopedias. His articles in the Athenian daily Elephtheria are so numerous that they would fill several volumes. Many of them are among the most profound written by a Greek. Most are concerned with religious themes, such as faith and reason, religion and philosophy, religious versus secular art, Byzantine iconography and music, the lives of Martyrs and other Saints, and so on.

Kontoglou won the Academy of Athens Prize for his book Ekphrasis, in 1961, and the Purfina Prize for his book Aivali; My Native Place, in 1963. The latter is the first volume of his Erga (“Works”) which began to be published by Astir Publishing Company at Athens in 1962.

In recognition of his great achievements as an author, the Academy of Athens, the highest cultural institution in Greece, awarded him on March 24, 1965, its Aristeion Grammaton, its highest prize in letters.

Kontoglou also carried on an enormous correspondence. He once told me that he wrote about fifty letters a month, corresponding not only with Greeks, but also Americans, Finns, Frenchmen, Germans, Russians, Ugandans and others. He had countless friends and admirers throughout the world who sought his guidance on iconography, and on Orthodox doctrine and living.

In Kontoglou’s writings, we encounter a man who has unshakable religious faith, free from all skepticism and metaphysical anguish. We encounter a man who is steeped in the Holy Scriptures and writings of the Eastern Church Fathers, particularly the great mystics such as Saint Macarios the Egyptian, Saint John Climacos, Saint Isaac the Syrian, Saint Symeon the New Theologian, and Saint Gregory the Sinaite. We find a man who has the profoundest respect for the Sacred Tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy, including all its dogmas, canons and sacred arts (architecture, iconography, music), tolerating no deviations. Orthodoxy was for him the sacred Kivotos, the sacred Ark, and these its precious contents, which must be carefully guarded and not cast away, or exchanged for counterfeits.

Kontoglou was strongly opposed to the participation of Orthodoxy in “ecumenism,” seeing in such participation the dangers of compromise on matters which admit of no compromise. He was especially critical of the maneuvers of Patriarch Athenagoras, in whom he saw an apostate . . . a betrayer of Greece and Orthodoxy. In his last book, entitled Ti Einai he Orthodoxia kai ti Einai ho Papismos (“What Orthodoxy Is and What Papsim Is”) Kontoglou stressed the abyss that separates Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism, which renders utterly absurd Athenagoras’s assertions that there are no real differences between the two.

Kontoglou was a man of adamantine Orthodox faith and impeccable character, adorned with the virtues of great humility, long-suffering, courage, wisdom, purity, hope and love. He was a devout man, a holy man, a man of God. All that he did bears the impress of these qualities.

As during his life, so at his death, it was evident that Kontoglou was free from worldly attachments, a citizen of the City of God, not of the earthly city, whose glory is temporary and whose power is doomed to pass away. He died poor, ignored by the State. His body was not accompanied to the grave by any State dignitaries, but only by friends and admirers, who loved him deeply.

By Dr. Constantine Cavarnos at Pemptousia