A Vigil

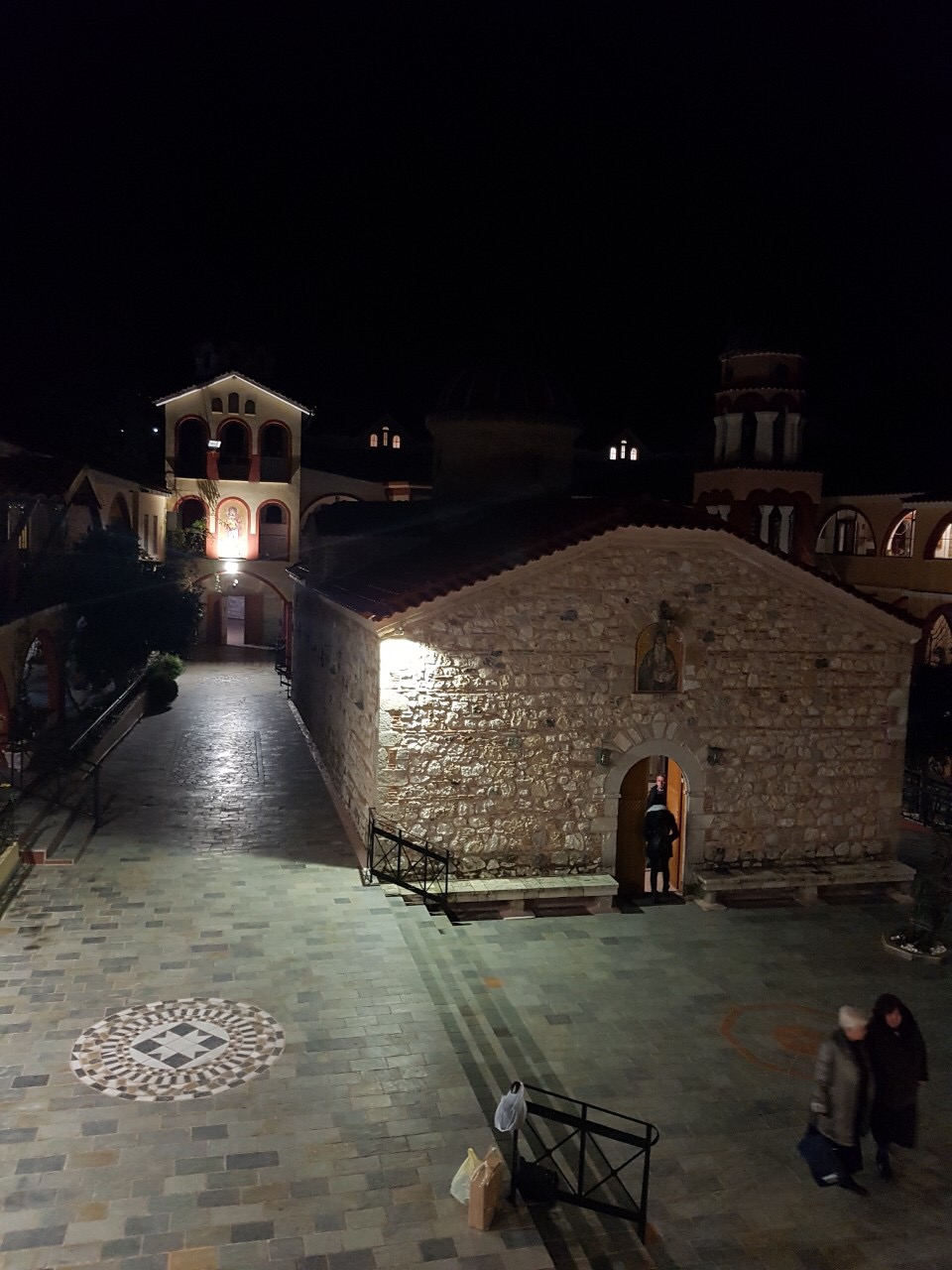

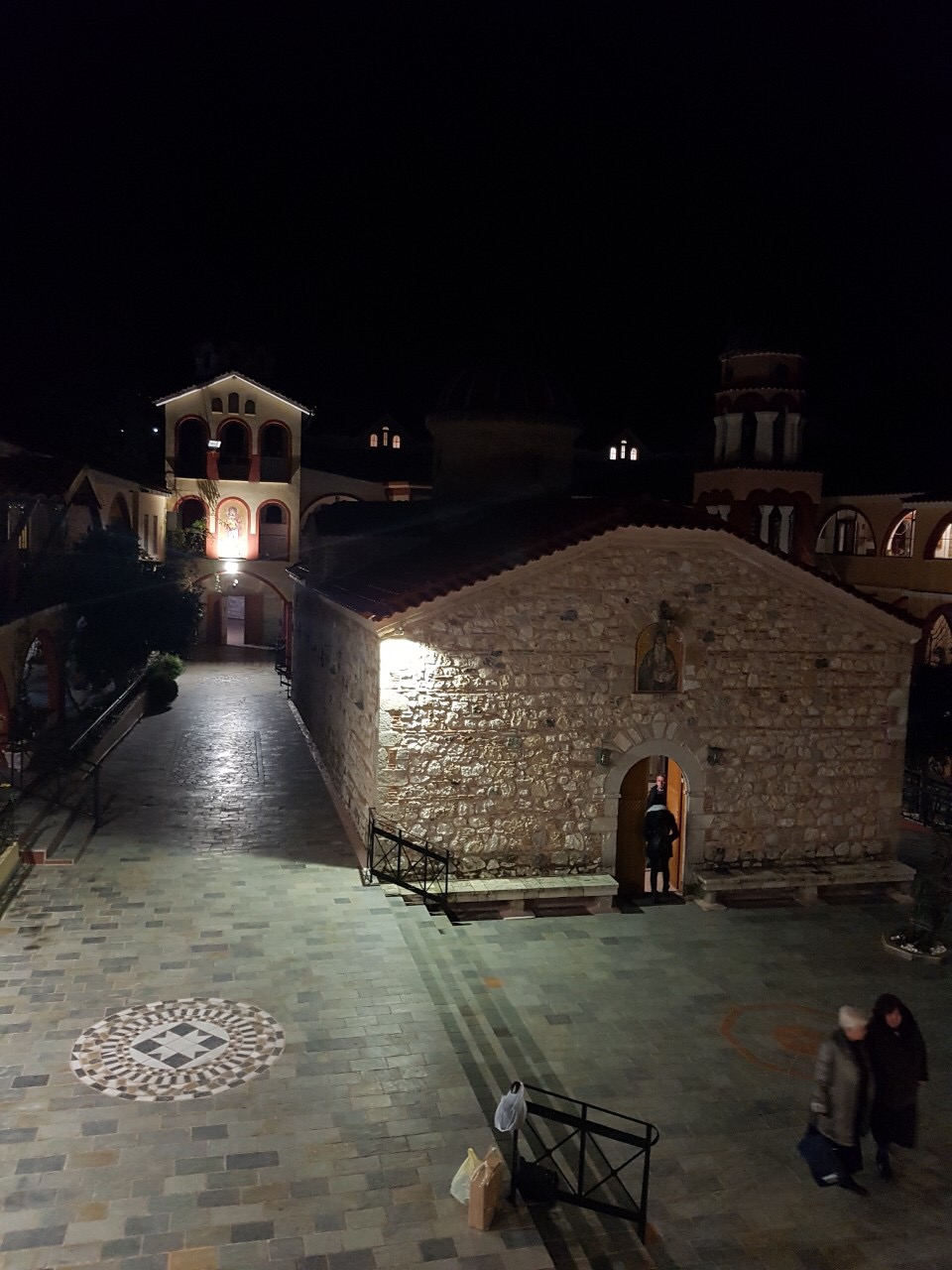

Elder Iakovos Tsalikis was one of the most important and saintly personalities of our day, a great and holy Elder. He was a vessel of grace, a living incarnation of the Gospel, a dwelling-place of the Holy Spirit and a true friend of God. From early childhood his aim was sanctification, and he enjoyed praying and would go to different chapels, light the icon-lamps and pray to the saints. In one chapel in his village, he was repeatedly able to speak to Saint Paraskevi. He submitted to God’s call, which came to him when he was still a small child, denied himself and took up the Cross of Christ until his last breath. In 1951, he went to the Monastery of Saint David the Elder, where he was received in a miraculous manner by the saint himself.

He was tonsured in November 1952. As a monk he submitted without complaint and did nothing without the blessing of the abbot. He would often walk four to five hours to meet his Elder, whose obedience was as parish-priest in the small town of Limni. The violence he did to himself was his main characteristic. He didn’t give in to himself easily. He lived through unbelievable trials and temptations. The great poverty of the monastery, his freezing cell with broken blinds and cold wind and snow coming in through the gaps, the lack of the bare essentials, even of winter clothing and shoes, made his whole body shiver and he was often ill. He bore the brunt of the spiritual, invisible and also perceptible war waged by Satan, who was defeated by Iakovos’ obedience, prayer, meekness and humility. He fought his enemies with the weapons given to us by our Holy Church: fasting, vigils and prayer.

Although he didn’t seek office, he agreed to be ordained to the diaconate by Grigorios, the late Bishop of Halkida, on 18 December 1952. The next day he became a priest. In his address after the ordination, the bishop said: ‘And you, son, will be sanctified. Continue, with God’s power, and the Church will declare you [a saint]’. His words were prophetic. He was made abbot on 27 June, 1975, by Metropolitan Chrysostomos of Halkida, a post he held until his death.

As abbot he behaved towards the fathers and the visitors to the monastery with a surfeit of love and understanding and great discernment. His hospitality was proverbial. Typical of him was the discernment with which he approached people. He saw each person as an image of Christ and always had a good word to say to them. His comforting words, which went straight to the hearts of his listeners, became the starting-point of their repentance and spiritual life in the Church. The Elder had the gift, which he concealed, of insight and far-sight. He recognized the problem or the sin of each person and corrected them with discretion. Illumined by the Holy Spirit he would tell each person, in a few words, exactly what they needed. Saint Porfyrios said of the late Elder Iakovos: ‘Mark my words. He’s one of the most far-sighted people of our time, but he hides it to avoid being praised’.

In a letter to the Holy Monastery of Saint David, the Ecumenical Patriarch, Vartholomaios, wrote: ‘Concerning the late Elder, with his lambent personality, the same is true of him as that which Saint John Chrysostom wrote about Saint Meletios of Antioch: Not only when he taught or shone, but the mere sight of him was enough to bring the whole teaching of virtue into the souls of those looking at him’.

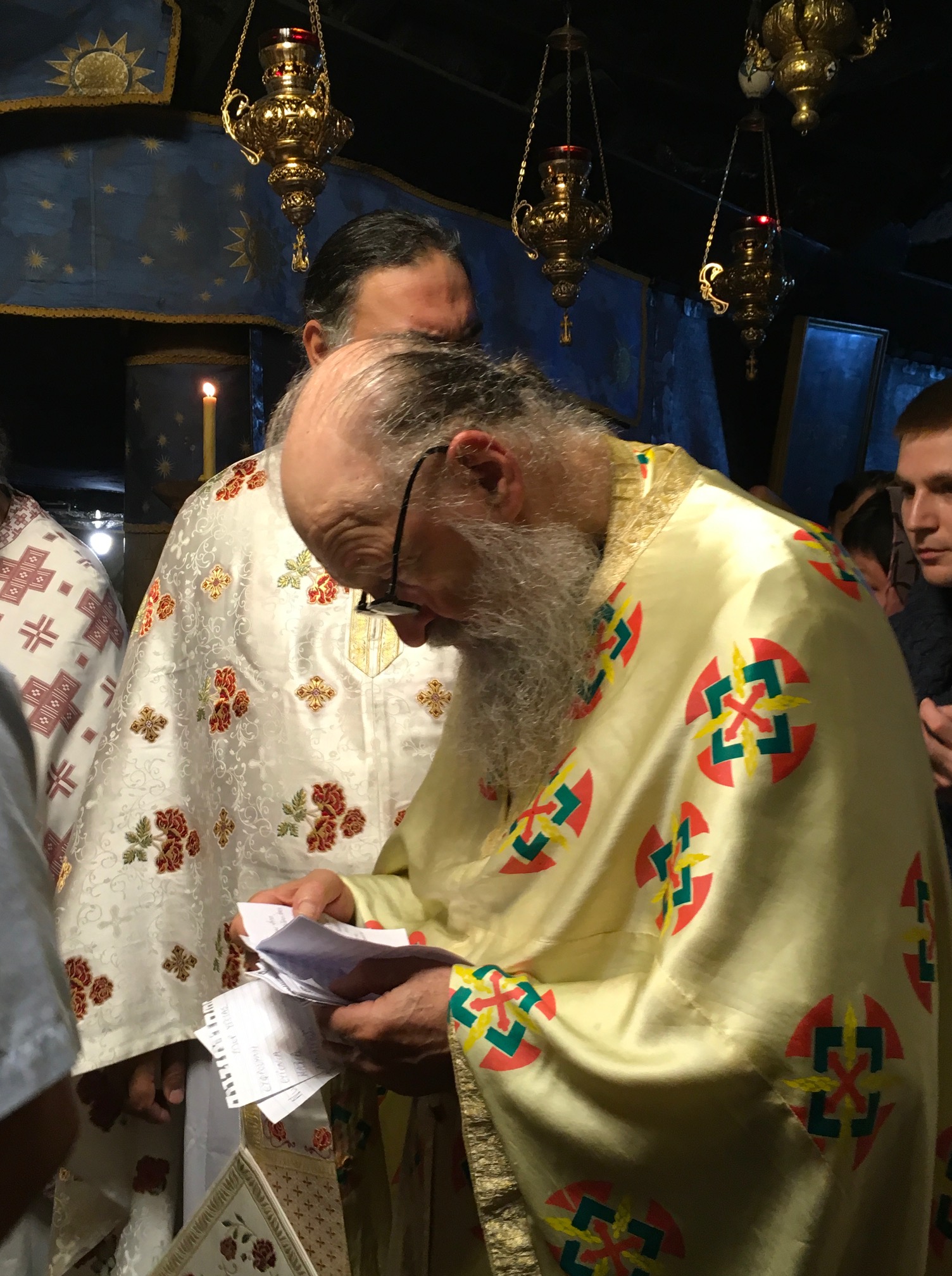

He lived for the Divine Liturgy, which he celebrated every day, with fear and trembling, dedicated and, literally, elevated. Young children and those with pure hearts saw him walking above the floor, or being served by holy angels. As he himself told a few people, he served together with Cherubim, Seraphim and the Saints. During the Preparation, he saw Angels of the Lord taking the portions of those being remembered and placing them before the throne of Christ, as prayers. When, because of health problems he felt weak, he would pray before the start of the Divine Liturgy and say: ‘Lord, as a man I can’t, but help me to celebrate’. After that, he said, he celebrated ‘as if he had wings’.

One of the characteristic aspects of his life was his relationship with the saints. He lived with them, talked to them and saw them. He had an impressive confidence towards them, particularly Saint David and Saint John the Russian, whom he literally considered his friends. ‘I whisper something in the ear of the Saint and he gets me a direct line to the Lord’. When he was about to have an operation at the hospital in Halkida, he prayed with faith: ‘Saint David, won’t you go by Prokopi and fetch Saint John, so you can come here and support me for the operation? I feel the need of your presence and support’. Ten minutes later the Saints appeared and, when he saw them, the Elder raised himself in bed and said to them: ‘Thank you for heeding my request and coming here to find me’.

One of his best known virtues was charity. Time and again he gave to everybody, depending on their needs. He could tell which of the visitors to the monastery were in financial difficulties. He’d ask to speak to them in private, give them money and ask them not to tell anyone. He never wanted his charitable acts to become known.

Another gift he had was that, through the prayers of Saint David, he was able to expel demons. He would read the prayers of the Church, make the sign of the Cross with the precious skull of the saint over the people who were suffering and the latter were often cleansed.

He was a wonderful spiritual guide, and through his counsel thousands of people returned to the path of Christ. He loved his children more than himself. It was during confession that you really appreciated his sanctity. He never offended or saddened anyone. He was justly known as ‘Elder Iakovos the sweet’.

He suffered a number of painful illnesses. One of his sayings was, ‘Lucifer’s been given permission to torment my body’. And ‘God’s given His consent for my flesh, which I’ve worn for seventy-odd years, to be tormented for one reason alone: that I may be humbled’. The last of the trials of his health was a heart condition which was the result of some temptation he’d undergone.

He always had the remembrance of death and of the coming judgement. Indeed, he foresaw his death. He asked an Athonite hierodeacon whom he had confessed on the morning of November 21, the last day of his earthly life, to remain at the monastery until the afternoon, in order to dress him. While he was confessing, he stood up and said: ‘Get up, son. The Mother of God, Saint David, Saint John the Russian and Saint Iakovos have just come into the cell’. ‘What are they here for, Elder?’ ‘To take me, son’. At that very moment, his knees gave way and he collapsed. As he’d foretold, he departed ‘like a little bird’. With a breath like that of a bird, he departed this world on the day of the Entry of the Mother of God. He made his own entry into the kingdom of God. It was 4:17 in the afternoon.

His body remained supple and warm, and the shout which escaped the lips of thousands of people: ‘Saint! You’re a saint’, bore witness to the feelings of the faithful concerning the late Elder Iakovos. Now, after his blessed demise, he intercedes for everyone at the throne of God, with special and exceptional confidence. Hundreds of the faithful can confirm that he’s been a benefactor to them.

Source: Pemptousia, “The Elder of love, forgiveness and discernment” by Alexandros Christodoulou

For more information about the monastery and St. David, go here