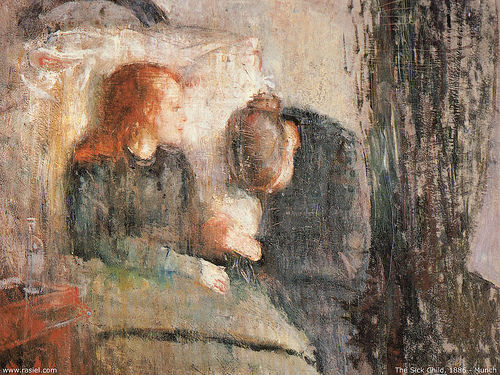

“The Dread Judgment “Day” will last as long as the Six Psalms last, a few minutes. At this time, while we will be judged, the Angels will chant the Six psalms. …

All the people who will be alive at this moment, they will instantly experience death and then be immediately resurrected. Our bodies will be immaterial, space-less. We will be able to see each other’s body and we will all be 33 years old.

![]()

Our Lord will hold the Book of Life, the Gospel, open, and immediately, each one of us will go on our own either to the right or to the left, because we will know in our hearts whether we are for Paradise or not.

![]()

This is exactly why in the Bishop’s throne, the Book in the icon of Christ is open and there is no candle over this icon–this indicates that there will be no Mercy in the Second Coming. While in the Iconostasis, the Book which Christ is holding is closed and there is a candle lit over the icon because there is still Mercy. “

✝️ Blessed Elder Amvrosios Lazaris the Athonite (21/12/1912 – 02/12/2006) ☦️

The Hieromonk Amvrosios (born Spyridon Lazaridis) departed this life on 2 December 2006 (New Calendar), at the age of 92. He was the spiritual father of the Holy Monastery of Our Most Holy Lady Gavriotissa, Dadi, and of thousands of Christians from all over Greece.

During a chat, I [Archimandrite Ephraim, Abbot of the Vatopaidi Monastery] once had with the late Elder, he told me that after his military service, he wanted to go to the Holy Mountain, but he didn’t know how or where to go. Then a young man of about 25 appeared and told him: “I know the place, come with me”. And so he went.

They set off together, went down to the harbour and embarked on a boat. “He gave me bread, as well”, he said, “and we ate together all the days I was with him. He didn’t tell me his name, though, and I didn’t ask. So we arrived at Dafni and from there walked on, further up the Holy Mountain.

When I was with him, I felt very safe. As we went along, he showed me the Monastery of Xiropotamou, where they honour the Forty Martyrs. He asked if I would like to pay my respects and I agreed to do so. We went into the katholiko, the main church of the Monastery, and when I kissed the icon, forty men appeared and surrounded us. The young man turned to me and said: “They’re the Forty Martyrs and they’re happy that you’re going to be a monk”.

From there we continued on our way and reached Karyes, and from there went to the Holy Monastery of Koutloumousi. The young man stopped, pointed out the monastery to me and said: “You’ll stay here, Spyro. You’ll become a monk. You’ll be patient and obedient to the Elder”. And he disappeared.

It would seem that this was an angel of the Lord, Spyridon’s guardian angel. Spyridon remained at this monastery as a novice, and, at the age of 25, became a monk with the name of Hariton.

… Elder Amvrosios was always in communion with the Saints. Once, “When I was in bed, in pain, I [Elder Amvrosios himself says] could see the chapel of the Holy Unmercenary Doctors opposite, and I asked them to help me. Two doctors appeared in white smocks and they tried to set my leg. ‘Pull, Kosmas’ said one. ‘Hold it here, Damianos’, said the other. In five minutes, the pain had gone and I was well again”. When the brethren in the monastery saw him completely well, they praised God and the Holy Unmercenary Doctors.

The blessed Elders Porfyrios Kavsokalyvitis († 02/12/1991) and Amvrosios the Athonite (†02/12/2006) together with some lay pilgrims on a visit.

Read more about Elder Amvrosios’ life, here

Lion, below fresco of St Mary of Egypt. Chapel of the Life Giving Spring, Evia, Greece. Aidan Hart. Fresco

Lion, below fresco of St Mary of Egypt. Chapel of the Life Giving Spring, Evia, Greece. Aidan Hart. Fresco

The Good News about the Birth of Jesus

The Good News about the Birth of Jesus The Baptism of Jesus

The Baptism of Jesus Jesus Calms a Storm

Jesus Calms a Storm The Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd Jesus Prays in Gethsemane

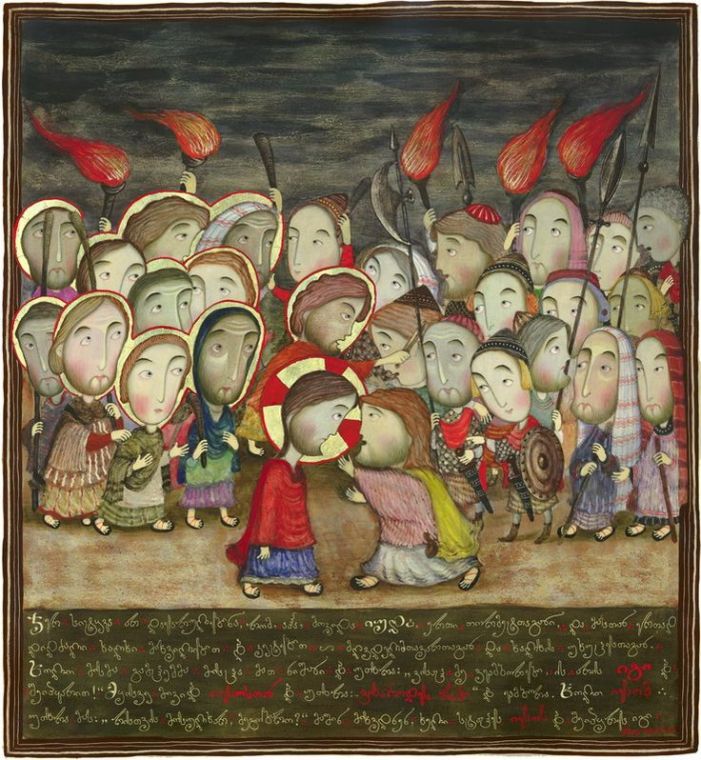

Jesus Prays in Gethsemane Carrying His Own Cross

Carrying His Own Cross